First time here? Read our "what is climate engineering" page.

Several climate engineering researchers have suggested alternative ways we might categorize different geoengineering techniques. Typically these suggest – among other things – making a clear distinction between solar radiation management (SRM) and carbon dioxide removal (CDR) techniques. Indeed the National Academies of Science took the decision to publish separate reports on each of these potential groups of intervention.

Some enthusiasts for enhanced effort to develop and deploy CDR technologies have seized on these suggestions to propose that we further distinguish CDR, by removing it altogether from the category of ‘geoengineering’. While I am an enthusiast for CDR myself, advocating serious effort in research, development and deployment in a range of sustainable and ethical CDR techniques, and advising groups as diverse as Friends of the Earth and the Virgin Earth Challenge to this effect, I have reservations about this proposal.

In caricature, the argument often runs as follows: SRM proposals are highly risky, almost entirely untested, and reasonably perceived as ‘nuts’. These characteristics dominate the public and political understanding of ‘geoengineering’ and thus reduce support and funding for CDR research and development at a time it is urgently needed. Further, it is pointed out that the enhancement of carbon sinks is already included in the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change agreements, and, moreover, that IPCC projections rely on unspecified negative emissions (often inappropriately assumed to be implausibly large deployments of Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS)) to prevent high probabilities of temperature rises exceeding 2oC. In this context, it is suggested, we should get on with the important business of developing CDR, and avoid the distractions that arise from it being labelled as geoengineering.

And the Paris deal raises the stakes. Restricting temperature rises to less than 1.5oC – a level widely considered to be less risky, especially for those countries most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change – implies a much larger requirement for CDR, and much earlier achievement of global net zero – possibly even before 2050. Any delays to the development of CDR would become highly problematic.

I have some sympathy for these arguments, yet there are a number of reasons – even with a 1.5oC target – why I suggest we should not rush too quickly to disentangle CDR from the broader idea of geoengineering.

First there is a procedural similarity between CDR and SRM: both are deliberate interventions to reduce the likelihood and extent of dangerous climate change undertaken after the greenhouse gases expected to drive dangerous change have been released. In other words they are remedial rather than preventative. It is true that CDR might well be better at this remedial task – by reducing GHG concentrations it not only reduces temperatures, but also ocean acidification, and better restores pre-existing precipitation regimes. SRM on the other hand would merely mask temperature increases, with limited effects on ocean acidification, and would create novel climate regimes across significant areas of the world, with new patterns and levels of precipitation. However it would almost certainly deliver its effects much more rapidly than CDR. Still, they are both responses to climate change rather than preventative measures.

There are a number of reasons – even with a 1.5oC target – why I suggest we should not rush too quickly to disentangle CDR from the broader idea of geoengineering.

Second, both sets of intervention also bring some similar ethical risks, such as potential for certain forms of ‘moral hazard’: the likelihood that rates of emissions mitigation will be lower than otherwise, in the belief that SRM or CDR can rectify the ‘overshoot’ at some future date. On balance I suspect the risk and temptation will be much higher for SRM, with its apparently low costs, than for CDR, but there is as yet no convincing evidence that policy makers would not choose to avoid tough choices today if they could promise to deploy more CDR in the future. In this respect both CDR and SRM can be seen as further extensions of the public and policy communities’ unwillingness to change behaviour and challenge the fundamental drivers of climate change in our over-consumption of fossil fuels. Both could undermine the delivery of commitments made in the international policy regime – especially in the continuing absence of legally binding targets or enforcement mechanisms.

Third, there are questions of risk and testing. It is true that more practical research has been done on some CDR techniques, but to imply that large-scale biochar or BECCS plantations, ocean iron-fertilisation (OIF), ocean alkalinisation or enhanced weathering by spreading rock dust over millions of square kilometres – to name but a few CDR options – are well tested and low-risk is (to put it bluntly), also ‘nuts’. To be fair, most advocates of CDR acknowledge the need for more careful testing, and argue rather that the definitional issue is preventing this necessary task; but there are also boosters out there who talk as if they have a silver bullet for climate change already in the chamber.

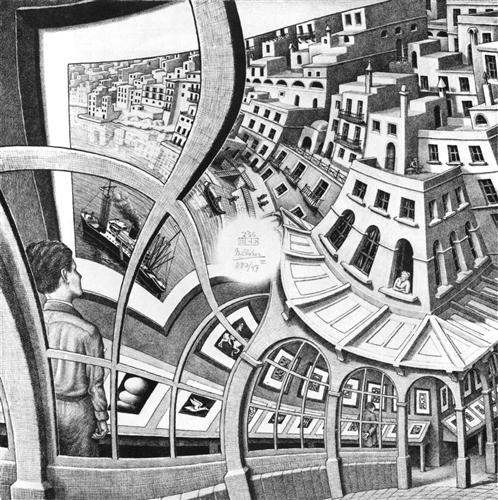

Determining boundaries can be difficult.

Finally though, it is also the case that the distinctions between SRM and CDR might not be as clear-cut as generally assumed. SRM techniques are likely to affect rates of carbon sequestration by biological systems. More diffuse light in higher CO2 conditions broadly promotes plant growth. Other effects of SRM are expected to reduce soil microbial respiration, enhancing carbon storage in soils too. That these biological and soil sinks would be relatively vulnerable to further disruption in the face of ongoing warming, or the ‘termination’ of SRM before mitigation has been completed, does not eliminate the CDR effect. Moreover, CDR techniques can affect temperatures via SRM mechanisms too: afforestation – at least in higher latitudes – reduces albedo, producing offsetting warming, while OIF releases dimethyl sulphides which could have a significant impact on temperatures by reflecting incoming sunlight (analogous to, if more short-lived, than the effect of sulphates in the stratosphere). More generally the earth-system side-effects of, and interactions between possible geo-engineering interventions are massively under-researched. In this respect, then it is too early to draw a bright line between the two broad categories.

In conclusion then, for definitional and governance purposes there are times when we will want to consider CDR and SRM techniques separately, and perhaps as Clare Heyward suggests, see these as categorically equivalent to responses such as mitigation and adaptation. There are also times when it is most appropriate to consider techniques in more specific detail, as Heyward also urges us to do – distinguishing OIF from DAC for example. This will be essential to distinguish sustainable and ethical options from the rest: for example, within BECCS, forest plantations that displace indigenous peoples to supply biomass power are unethical, yet adding carbon capture to existing pulp and paper production might be sustainable. So if CDR generally remains part of a category considered undesirable, that simply ensures that we enthusiasts have to make a strong case for the specific forms that are fair and sustainable. Finally, and critically, there remain other occasions when we need to be aware of and seeking to manage common ethical and physical issues that arise from geoengineering interventions in earth-systems as a whole.

For my part I think we need a lot more careful research across the whole panoply of possible techniques; and carefully targeted policy and funding effort to develop and deploy selected CDR techniques in a timely fashion, alongside governance frameworks that minimize the effects of moral hazard. Then CDR could play a properly complementary role to rapidly accelerated mitigation and properly funded adaptation, in helping deliver climate justice.

As a postscript I want to briefly look at this from a different perspective. I fear that in some expressions the proposal to redefine CDR as ‘not geoengineering’ illustrates the technocratic and post-political blinkers that pervade climate engineering. Natural scientists who think they know best are easily tempted to believe that the public and politicians will suddenly be convinced by rational argument if we can just get past the worrisome terminology. But public concerns and controversy can’t be defined away by a change of name. If anything such efforts can make things worse, by implying that there is something to hide …

This post is part of a series. A response to this piece can be read here.

Duncan McLaren is a part time PhD student at Lancaster, UK. Alongside his PhD studies, on the justice implications of geoengineering, he consults and advises in a range of sustainable development, energy and climate change issues. Amongst other roles he served on the UK Research Councils’ stage-gate panel for the Stratospheric Particle Injection for Climate Engineering (SPICE) project review and is a member of the Integrated Assessment of Geoengineering Potential (IAGP) project advisory group. Duncan’s blog can be found here.

The Forum for Climate Engineering Assessment does not necessarily endorse the ideas contained in this or any other guest post. Our aim is to provide a space for the expression of a range of perspectives on climate engineering.